When it comes to apps, developers still tend to turn to Apple's iOS first, despite Eric Schmidt's prediction. Photograph: Justin Sullivan/Getty Images

As Apple prepares for a full week in which it will fete and educate the developers who write apps for the iPhone and iPad (and also its Mac computers) at its annual Worldwide Developers Conference (WWDC) in San Francisco - and with Google preparing to do the same for those writing Android apps at its I/O event on 27 June - the question many are asking is: if Android phones outsell iPhones, why do developers still prefer to write for Apple first?

It wasn't expected to be this way. Speaking at the LeWeb conference on 7 December 2011, Google's executive chairman Eric Schmidt was in ebullient form as he considered the success of Google's Android mobile operating system. "Android is ahead of the iPhone now," he told the audience of techies and entrepreneurs. Ahead in terms of the number of phones, the quality of the software, the lower price, and having more companies making devices that used it, he said.

He also had some predictions: "Ultimately, application vendors are driven by volume, and volume is favoured by the open approach Google is taking," he said. "There are so many manufacturers working so hard to distribute Android phones globally that whether you like ICS [Ice Cream Sandwich, the name for version 4.0 of Android, released in October] or not… you will want to develop for that platform, and perhaps even first."

When one Android user told Schmidt it was frustrating to see iPhone and iPad - known as "iOS" - versions of apps coming to market before the Android one, Schmidt said that in part because of the new software, "my prediction is that six months from now you'll say the opposite". That is, that Android versions of particular products would be written before the iOS ones.

Calendar time

Six months later, there are few signs of that happening. Instead, even while the number of Android phones in use has continued to grow steadily, to more than 300m, and with Android phones making more than 50% of the 150m-odd smartphones sold worldwide every quarter, developers still look to Apple's platform first.

It's not initially obvious why. A huge number of apps are being launched on Android. Analytics firm Distimo, which tracks the various app stores, reckons that in the first four months of 2012 more than 100,000 apps were added to the Google Play store, versus 63,000 for Apple's App Store. Microsoft's Marketplace, for Windows Phone, and BlackBerry's official stores added 35,000 and 22,000 respectively in the same period.

But follow the money - a big factor for the important developers, who can easily spend thousands writing a new app - and it's a different story. Distimo and analyst firm CCS Insight launched their App Vu Global service in early April 2012, tracking downloads and revenues from the app stores. Its initial findings claimed that Apple's App Store is generating $5.4m every day in app sales for the top 200 grossing iPhone and iPad apps. For Google Play, their estimate was just $679,000 for the top 200 grossing apps on Google Play, or about 12% of Apple's revenue.

Another mobile app-tracking service, Flurry, noted on 7 June that "For every ten apps that developers build, roughly seven are for iOS." Though the total volume of apps being developed has doubled - from over 9,000 in the first quarter of 2011 to more than 18,000 in the second quarter of 2012 - that 7:3 ratio in Apple's favour has remained consistent.

Part of that has been because iPhone users have shown themselves willing to pay for apps in a way that Android users so far have not. In January 2012, Apple said that since 2008, when its App Store opened, developers had been paid a total of $4bn, of which more than $700m was paid in the last quarter of 2011 alone. Google hasn't given a comparable figure, though Horace Dediu, who runs the Asymco consultancy, puts the figure for Google's total app sales in 2011 at $300m - meaning developers would get $210m in total.

In March 2012, Flurry crunched data from developers using its tracking tools in their apps, and claimed that given the same number of users per platform, a developer who got $1 on the iTunes App Store would get $0.23 from Google Play.

Nine-year headstart in credit cards

That's a key pointer to why developers don't look to Android first. Some cases are simple examples of what economists call "opportunity cost". Dave Addey is managing director of Agant, a British software developer which has written, among others, the Train Times app which costs £4.99 on the iPhone, and uses National Rail data to offer real-time data feeds, plan journeys and show timetables. "We still prioritise iOS," he says. "Because it's the main platform on which people will pay for an app. We haven't done Android apps for business reasons. It comes down to this: do you port [translate] to Android, or do you develop another app for iOS? In the end, iOS is the better business case. Apple's greatest trick has been making it really easy to pay for apps. Once you have your iTunes account, you just enter a password." Google is trying to emulate that by encouraging people to add a credit card when they first set up a phone; but it is coming from a long way behind Apple, which started its iTunes Music Store selling music online in 2003, and is now one of the web's biggest five holders of credit card details, along with Amazon, eBay and PayPal.

Addey points to the problems encountered by Imangi Studios, developer of the hugely popular Temple Run game - in which you are pursued along stone-lined routes by fast-moving unseen monsters - when it ported the app to Android, releasing it at the end of March.

It was a huge success in terms of downloads, hitting 5m in about 10 days. But Imangi Studios - a husband-and-wife team, plus a designer - soon discovered that Schmidt's promise of Android being ahead in the number of phones and manufacturers was only too true. Despite writing it to run on 707 Android devices, they said that 99% of the emails requesting support were actually complaints that it wouldn't run on the user's particular phone model or version of Android. They were pilloried on Facebook, despite having what would be regarded by anyone as a successful release.

Breaking up is easy

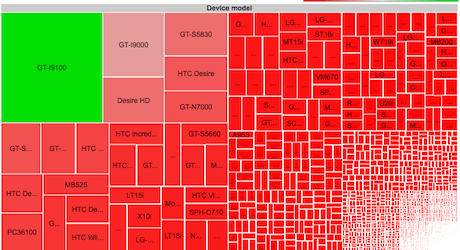

Those subtle differences between devices are known in the industry as "fragmentation". While Apple does have some fragmentation - there are seven models of iPhone, three different iPads and four of the non-phone iPod Touch - they pale into insignificance compared to Android's, where OpenSignals, which provides a network coverage app, recently found 1,363 device models running Android, from 599 different brands - though Samsung dominates with about 40% of the market.

Android fragmentation, as perceived by OpenSignals based on devices downloading its Android app. Click for original post.

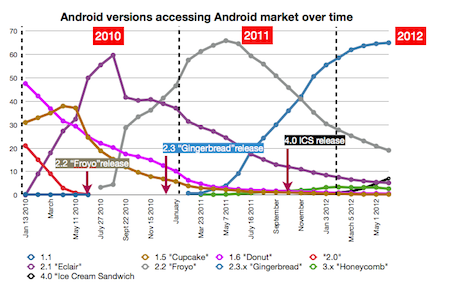

Android fragmentation, as perceived by OpenSignals based on devices downloading its Android app. Click for original post."It's a problem, especially for testing your app," says Agant's Addey. "You need to get a representative set of [Android] handsets so you can try it out. But that makes it hard to create a best-of-breed app because of the fragmentation, and because people are less likely to have the latest version of the [Android] software. You have to build to the lowest common denominator, rather than using the latest features." Google's statistics to the beginning of June say that just 7.1% of phones actively using its Google Play app market run version 4.0, or "Ice Cream Sandwich". The most-used version is 2.3, or "Gingerbread", released in December 2010, running on 65%; in total, 84.1% of devices using Google Play run Android version 2.3 or 2.2, dating back to June 2010.

Google Play: proportion of devices running different versions of Android accessing within 14-day period, since January 2010. Source: Google

Google Play: proportion of devices running different versions of Android accessing within 14-day period, since January 2010. Source: GoogleBy contrast, although Apple's oldest handset on sale - the iPhone 3GS - dates to June 2009, before Android 2.2, it can run the latest version of iOS – so app developers can target apps at features it includes, confident the majority of users will be able to run them.

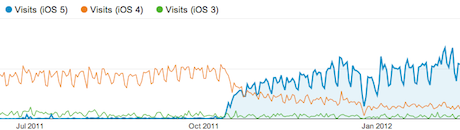

And iPhone users definitely do update. Addey points to data for the UK Train Times app, which is available for every iPhone and iPod Touch ever made. The latest version of iOS, v5, was released in October 2011: Addey saw the proportion of devices using the preceding version, iOS 4, drop dramatically - while the proportion using iOS 5 leapt.

Update fever

iOS versions accessing UK Train Times app feed, by time. Source: Agant. Click for larger version with longer time series

iOS versions accessing UK Train Times app feed, by time. Source: Agant. Click for larger version with longer time seriesNow, just under nine months since iOS 5's release, 86.2% of devices using the Train Times app run iOS 5, 12% use iOS 4, and just 1.7% use iOS 3 (released in 2009). Other developers put the proportion of iOS 5 users at 75% - lower, but still overwhelming.

"Compare this to the 7.1% uptake of Android 4.0, and it's pretty easy to see why we develop new apps for iOS first," Addey says. "Apple is constantly pushing its users and developers to be running the latest versions." He says Agant has tended to focus on bigger apps, "because we know we can support the latest features from Apple." The team's latest product is a World War 2 app for the iPad which includes a day-by-day timeline that interacts with a map, Pathe newsreel videos, and commentary by the historian Dan Snow.

There's no a priori reason why Apple should be able to get updates out more quickly. Changes to the "baseband" software which operates the radio systems in mobile phones (to connect to networks) have to be tested and approved by phone carriers; Apple has to go through those just like Android handset makers. Such changes are part of every major version both of Android and iOS.

But Apple has a clear incentive to roll out updates - to keep users and developers happy - whereas carriers and Android handset makers are less eager; fragmentation and opportunity cost hits them too, and they may have more incentive to encourage people to buy a new handset than see them using the same one with newer software.

Putting kids first

However, generalisations about what "developers" are doing in terms of platform support are risky. In key fast-growing categories – particularly free-to-play social mobile games – a number of companies launch new titles simultaneously on iOS and Android, or even on Android first. Glu Mobile, TinyCo, Storm8 and TeamLava, who have some of the most lucrative iOS games according to Apple's "top grossing" chart, are also fixtures on Android. Some companies are adopting an Android-first strategy here too.

Japanese social games publisher DeNA, which recently reported revenues of $529m for the first quarter of 2012 alone, chose Android as the platform to launch its Mobage community globally in 2011. Its recently-released Rage of Bahamut game is on Android but not iOS yet.

US publisher Pocket Gems launched a game called Tap Dragon Park exclusively for Android in May. Another US studio, Bionic Panda, focuses on Android games rather than iOS.

Certain kinds of apps can only work on Android rather than iOS, too. British startup SwiftKey is a good example: its natural-language keyboard app SwiftKey X has notched up millions of paid downloads on Google's store. It works by replacing the default keyboard on Android devices – which Apple does not allow on iOS.

"The early adopter community on Android is quite tech-savvy, and very keen to shout about the latest thing that they've discovered," says Ben Medlock, chief technology officer at SwiftKey. "We're one of the rare paid apps which is making money on Android."

Other app categories remain dominated by iOS – for example book-apps and children's apps. Swedish developer Toca Boca recently passed its 20 millionth kid-app download on iOS, but chief executive Bjorn Jeffery outlines the reasons it has so far shunned Android.

"It is a highly fragmented ecosystem to develop for, and the business model for upfront sales of apps still has its issues," he says, pointing to a question of how to allocate resources. "The answer there is unique to each developer, but I don't see 'Android first' becoming something strong in the kids app community within a foreseeable amount of time."

Resources are at the heart of why Schmidt's hopes that more companies would put Android first are currently certain to be disappointed. Toca Boca, Instagram, Temple Run... These companies were well aware of strong demand on Android for their apps, and they all knew they could probably make money there. But, faced with a decision to double down on iOS or put already-stretched resources into Android, they prioritised Apple's platform.

Volume, scale, or revenues?

Schmidt's bold statement that "application vendors are driven by volume" was, it turns out, inaccurate. True, the economics for certain kinds of apps – particularly free and social ones – are driven by scale. Yet the majority of app developers are driven by two simple motives: where they see the most revenues, and by the constraints of their resources and team size. And both those presently favour Apple - substantially.